Background

Brisbane was experiencing an unprecedented construction and infrastructure boom during the 1880s, as it evolved from a frontier town into a colonial city. The people were convinced of the unlimited potential of Queensland. This optimism drove prodigal loan spending, inflated land values and an influx of capital from the United Kingdom. This meant that sandstone opulence neighboured flimsy verandas and these homes fronted muddy roads. The resident could attend high-class theatre productions, sporting events, and extravaganzas.

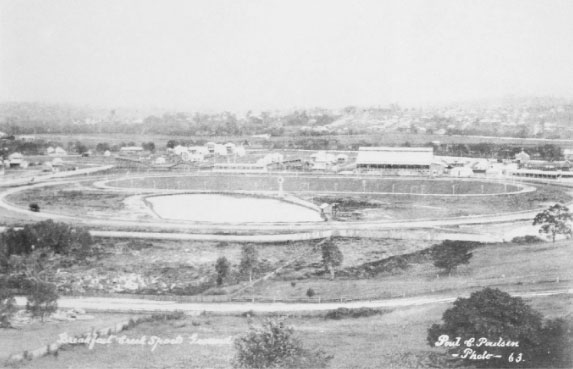

The Breakfast Creek Sports Ground in the 1880s

(John Oxley Library, Howell et al. 1989: 10)

1880s

Brisbane's 30 years of rapid economic growth which had commenced in 1861 peaked in the 1880s as the frontier town transitioned into a diverse and sophisticated colonial city. At the time, Queensland was believed to be a colony possessing unlimited land, resources, and agricultural, pastoral, maritime and commercial potential.

Greater Brisbane's total population increased from 37,053 in 1881 to 101,544 by 1891. Of this population, 93.7 per cent were of Anglo-Saxon/Celtic origin. The percentage of Brisbane's population of Chinese origin was 0.37 in 1881, 0.55 in 1886, and 0.45 in 1891.

By 1880, gas street lighting was commonplace in the city, and was being extended to the suburbs. In 1883, electricity was supplied to the Government Printing Office. Electricity had replaced gas for street lighting throughout greater Brisbane by the early 1890s.

Brisbane's suburban railway system expanded to Sandgate in 1882, Oxley in 1883, and Logan in 1885, with Brisbane's Central Station also completed that year. Brisbane's first tram line opened in 1885 running from Victoria Bridge to the Exhibition and Breakfast Creek, within a short walking distance of the Holy Triad Temple construction site.

The horse-drawn tramway system opened with the arrival of nine cars built in New York and nine built in Philadelphia. The highly polished cedar and mahogany cars mounted on steel springs were promoted as making motion almost imperceptible. The cars were drawn by two horses, with a third 'tip horse' attached to double-decked cars travelling steep grades. The tram system was seen as ushering in a new era of rapid development, enabling the colony to keep pace with a 'fast age’.

The 1880s saw one of Brisbane's biggest building booms with the erection of public and private buildings including the Government Printing Office, the Customs House, the first wing of the Treasury Building, and the Alice Street facade of Parliament House, the South Brisbane Town Hall, and the Queensland National Bank. The bank was hailed at the time as one of the finest examples of banking architecture in the world.

St Patrick's Catholic Church in Fortitude Valley, St Paul's Presbyterian Church in Spring Hill and St Andrew's Church of England in South Brisbane, were each constructed during the 1880s.

Victorian opulence in the form of ostentatious construction extended to commercial buildings, city offices and retail stores; to palatial banks, a host of hotels, four and five storey warehouses, imposing insurance offices and to theatres.

Brisbane's construction boom was underpinned by prodigal loan spending, the inflation of land values, and an influx of private capital from the United Kingdom. Construction was driven by optimism of future continued growth. Sandstone structures with colonnades and balconies often fronted on muddy and unpaved roads, and had shops with flimsy veranda posts used for tethering horses for neighbours.

References

- Crook, DP. 'Aspects of Brisbane Society in the Eighteen-eighties', Honours. The University of Queensland, 1958, p. 50.

- Howell, M, R Howell and DW Brown. The Sporting Image: a pictorial history of Queenslanders at play. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1989.

Two men preparing to play the gong.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

For most Chinese arriving in the colony through Brisbane during the second half of the 19th century, Brisbane lacked appeal. The city was seen as a transitory stopover on their journey north.

The first 56 Chinese to come to Brisbane on the Nimrod in 1848 arrived as indentured labourers on five year contracts for work as shepherds, outback handymen and on the waterfront. Brisbane's Chinese population remained relatively small throughout the remainder of the 19th century, working as furniture makers, domestic servants, market gardeners, hawkers and commercial traders.

During the 1880s, the percentage of Brisbane's population born in China remained close to half of one per cent. These relatively few Chinese settled in Brisbane were Cantonese from five distinct clan groupings, of which they divided into three groups: the Dongguan, the Zhongshan and the Siyi, being a combination of people from the remaining clans.

Young Chinese girl in front of the Holy Triad Temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Construction of the temple was the vision of financial trustees Chick Tong, George Shue, Way Hop, Wam Yo and Tong Wah in an attempt to unite the five clans by providing a common community focus. To achieve this, the Buddhist temple remained open to Confucian Chinese. However, the unification of the clans would take time to be achieved.

An 1892 investigation by Alfred Archey into complaints from Brisbane’s Siyi that they were suffering continuous violent assaults by members of the Dongguan revealed the extent of clannish divisions in Brisbane’s Chinese population. Archey described the factions as not being friendly to each other. He considered the largest group, the Dongguan, as very treacherous.

Alfred Archey noted the 300 to 400 Dongguan were led by Fat Kee, Way Ling Loong and Wong Fun. The approximately 200 Zhongshan men's leaders were H. Yeteng of 139 Wickham St, the Valley and the photographer Mr War Sing. The 40 to 50 Siyi were led by Oh Ark, Hing Kee and Ah Foo.

The Dongguan were always found to be the aggressors when prosecuted, even indicating who their victims would be prior to their assaults. The Dongguan then managed to follow through on their threats against all precautions.

Chinese women burning incense sticks.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The Dongguan had commenced a subscription of £2 and upward each to pay court fines and legal fees for men prosecuted for these assaults. They had also established a £5 payment for any Dongguan assaulting a Siyi and £20 for breaking limbs. While the Dongguan believed the only penalty for assault would be a fine, they had established a £1 per week retainer for any members who were imprisoned. A further agreement was in place for assaulting any interpreter or witness acting in a case against them.

References

- Archey, A (testimony). Queensland State Archives. Item ID 86513, Correspondence, Police, 1892

- Brandle, M (ed.). Multicultural Queensland 2001. Multicultural Affairs Queensland Community Engagement Division, Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Brisbane, 2001.

- Cronin, K. '"The Yellow Agony": Racial attitudes and responses towards the Chinese in Colonial Queensland', in R Evans, K Saunders, K Cronin (eds.), Race relations in colonial Queensland: a history of exclusion, exploitation and extermination, 3rd edn. University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1993, p. 237.

- Crook, DP. 'Aspects of Brisbane Society in the Eighteen-eighties', Honours. University of Queensland, 1958, p. 50.

- Fisher, J. The Brisbane overseas Chinese community 1860s to 1970s: Enigma or conformity, PhD. University of Queensland, 2005, pp. 32-33.

- Ip, D. 'Chinese', in M Brandle (ed.), Multicultural Queensland 2001. Multicultural Affairs Queensland Community Engagement Division, Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Brisbane, 2001, pp. 63-65.

- Lilley & O'Sullivan. Queensland State Archives. Item ID 86513, Correspondence, Police, 1892.

- Queenslander. 30 January 1886, p. 186.

- Queensland Figaro. 4 December 1902, p. 3 (7).

- Queensland Heritage Register. The Holy Triad Temple ID: 600056, 2013.

- Rains, K. 'The Chinese question'. Queensland Historical Atlas, 2010.

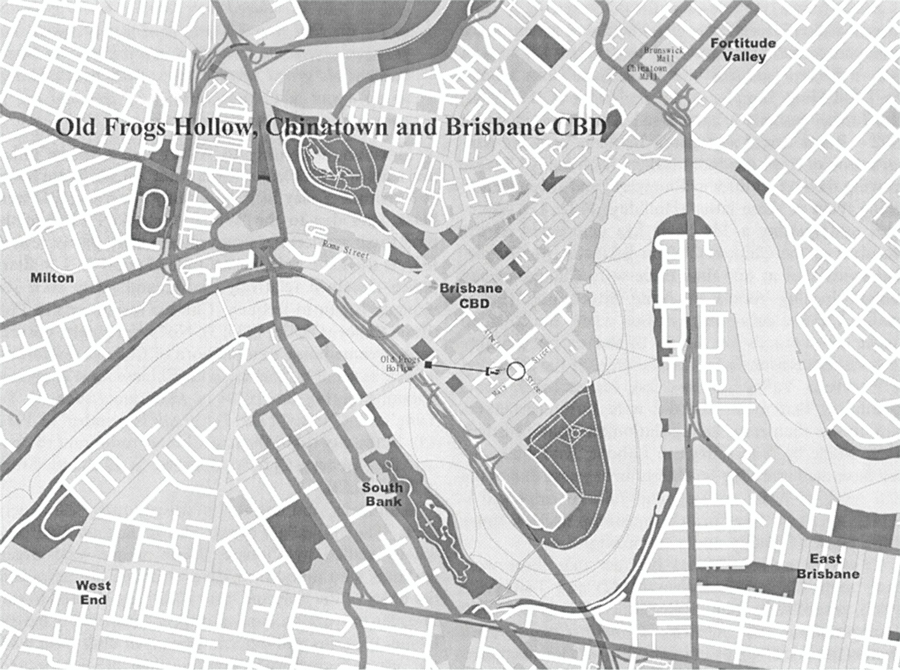

Map of Brisbane.

(John Oxley Library, Ip 2005: 67)

Sizeable numbers of Cantonese settled in Brisbane in the 1880s. Brisbane's Chinese migrants predominantly established businesses in a district then known as Old Frog's Hollow, within Brisbane's present-day CBD. These Chinese shops, small businesses and residences were known as the Chinese Quarter. They were mostly on the north side of Albert Street between Charlotte and Mary Streets, and extended around the corner into Mary Street.

Although the Chinese Quarter was considered unsanitary and renowned for opium and gambling, it remained frequented by local and visiting Europeans. Large Chinese retail and manufacturing businesses were also located in George, Queen and Elizabeth Streets in the city, and in Ann and Wickham Streets in the Valley.

Beyond the Chinese Quarter of Old Frog's Hollow, the City centre and the Valley, Chinese migrants had established market gardens as far afield as Ashgrove, Everton Park, Kedron, Eagle Farm, Sandgate, Nudgee, Toowong and especially on the flats around Breakfast Creek and Eagle Farm. By 1888, Brisbane depended almost entirely on these Chinese market gardeners for its supply of fresh vegetables.

The opening of the Holy Triad Temple at Breakfast Creek in 1886 saw it become a popular gathering place for greater Brisbane's Chinese community. Many of the market gardeners chose to bring their wares to the Roma Street Markets via the temple after the completion of a new metal Breakfast Creek bridge in 1889.

References

- Brandle, M (ed.). Multicultural Queensland 2001. Multicultural Affairs Queensland Community Engagement Division, Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Brisbane, 2001.

- Ip, D. 'Chinese', in M Brandle (ed.), Multicultural Queensland 2001. Multicultural Affairs Queensland Community Engagement Division, Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Brisbane, 2001, pp. 65-66.

- Queenslander. 12 May 1888, p. 746.

- Queensland Heritage Register. The Holy Triad Temple ID: 600056, 2013.

It is possible that the man holding the flag in the 1886 image is Sum Chick Tong.

(John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 10124, 2013)

Sum Chick Tong was born in 1849, and died in 1902. Chick Tong married an English woman named Gladys and they resided in the leafy outer suburb of Swan Hill (Kelvin Grove). Chick Tong and Gladys' son Sun Kum Chee (Shum Chick Tong) was born in Brisbane in 1885, but spent 1890 to 1911 in China receiving a Chinese education. Chick Tong became naturalised 1893.

Portrait of Sum Chick Tong and wife Gladys.

(John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 150952, 2013.)

Chick Tong was Brisbane's preeminent Chinese businessman during the 1880s. In 1884, Chick Tong established and controlled Brisbane's most prominent importing and trading firm, Kwong Nam Tai & Co., maintaining two shops in Queen Street, one in Albert Street, and a store in Stanthorpe. The significance of Chick Tong's position in Brisbane society enabled him to play a pivotal role in the planning, approval and construction of the Holy Triad Temple. At its opening, Chick Tong was the leader of the Chinese community and the prime trustee of the temple; however, after 1886, Chick Tong played no further leadership role in the Chinese community.

Photograph of Sum Chick Tong with his son Shum Chick Tong, prior to his son returning to China for study. c.1886.

(John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 197082, 2013.)

Through Kwong Nam Tai & Co., Chick Tong was responsible for importing the temple's elaborate roof from China. During the temple's opening ceremony, Chick Tong led the dignitaries with his personal £50 green silk flag, replete with striking colour and workmanship. The flag represented the Royal Dragon of the Chinese Empire, and was hoisted up a centre flag pole, between the temple's two red flags with white mitred borders.

In 1888, Kwong Nam Tai & Co. was the main target of the 1000 strong mob during Brisbane's race riot. Kwong Nam Tai & Co. was also the only Chinese business protected by the police. By the following year, the lingering effects of the riot had played a pivotal role in closing Kwong Nam Tai & Co.

A meeting of Kwong Nam Tai & Co.’s creditors met on Thursday 12 September 1889 to address the company's insolvency. The firm's insolvency was credited to a depression in trade, an inability to collect outstanding debts, interest rates of up to 60 per cent on loan repayments, losses during the 1887 floods, reduction in business due to rising anti-Chinese sentiment after the 1888 riot, and mismanagement of the Stanthorpe store. During the meeting, creditors who had previously felt great sympathy for Chick Tong, and guaranteed his word as unquestionable, came to accuse him of swindling. Chick Tong was accused of lying to his creditors, as his lack of stock contradicted his claims of no sales.

Kwong Nam Tai Teahouse

(Figaro, 14 January 1888, p.76)

In an example of racial profiling at the time, some consideration was granted that if Chick Tong had been European, he may have been able to give a good explanation for his actions. To this, one creditor demanded an explanation, claiming that Chick Tong was as good as any European in the English language and in accounting. It was suggested that Chick Tong's Jewish money lenders had taken all his stock when he failed to meet repayments. This assumption satisfied the creditors. By the meeting's close, a motion to liquidate rather than go into insolvency was put forward and was unanimously carried.

Sum Chick Tong died Sunday 30 November 1902, in an ambulance on his way to hospital. It is notable that Queensland's most racist and anti-Chinese newspaper, Queensland Figaro, remembered him not only as a Queen Street businessman, but also for being a liberal supporter of the Breakfast Creek Joss House, and for his charity to the poor, when he possessed the means.

References

- Brisbane Courier. 13 September 1889, p. 6.

- John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 10124, 2013.

- John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 150952, 2013.

- John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 197082, 2013.

- Queenslander, 30 January 1886, p. 186.

- Queensland Figaro. 14 January 1888, p. 76.

- Queensland Figaro. 4 December 1902, p. 3 (7).

- Queensland Heritage Register. The Holy Triad Temple, ID: 600056, 2013.