Construction

A committee of Brisbane’s leading Chinese businessmen collected funds for the temple’s construction. They were attempting to unite Brisbane’s five adversarial Cantonese clans within a shared place of worship. The rendered brick walls and a section of the floor were constructed by J Petrie & Son to plans drawn by a Chinese architect. All other woodwork, the triple roof and ornamentation were imported from China and completed by Chinese artisans. In the 1970s, the present caretakers residence and an additional Buddhist shrine were constructed on the western side of the temple.

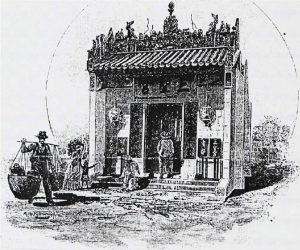

Drawing of the Holy Triad Temple

(Andrew Garran, Australasia Illustrated, vol.3, Picturesque Atlas Publishing Co, Sydney, 1892, p.1430.)

In the final two weeks prior to the temple opening, the roof glazing was yet to be installed, and the interior had not yet reached completion. A fresco painting was still being completed, and seven or eight men were busy in the final stages of construction. However, the alter at the northern end, the detailed fresco, and the craftsmanship of the interior woodwork were already receiving high praise from the media.

Construction of the Holy Triad Temple commenced in 1885 on land owned by George Shue, and was completed in late-January 1886. A committee of Brisbane's leading Chinese businessmen, including Chick Tong, George Shue, Way Hop, Wam Yo and Tong Wah, had collected funds for the temple's construction from the members of Queensland's Chinese community. The cost of constructing the temple must have been substantial; however, no indications of how the money was raised remain. The intention was to create a place of common worship that would unite the five Cantonese clans living in Brisbane.

All elements of the temple, including architecture, internal and external decoration and contents, the materials used, the colours chosen, and the deities, symbolise aspects of Chinese culture. The principles of feng shui determine the building be orientated north to south, with the entrance facing the south. Thereby, the entrance is open to the sun-orientated principle of yang, while the solid wall deflects the cold principle of yin.

Plan showing Joss House and proposed surroundings.

(Fisher, J. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.)

Floor plan of Breakfast Creek Temple.

(Fisher, J. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.)

The temple is a rectangular shape, constructed using bricks rendered with cement both inside and out, and whitewashed on the exterior, with a tile and cement grouted floor. The walls and a section of the floor were constructed by John Petrie & Son to plans drawn by a Chinese architect in a plain English style of architecture. This may be the only example in Australia of a Chinese community employing such a prominent Australian building company to construct their temple. However, all the woodwork, the roof, and the ornamentation were tasked to Chinese artisans brought from China for the specific task of the temple's construction. The artisans returned to China on the temple's completion.

Drawing of roofline of the Temple.

(Fisher, J. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.)

Drawing of the three sections of the building.

(Fisher, J. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.)

The complex triple roof was designed in a traditional style, appropriate to the temple's purpose, and imported from China by Brisbane's most prominent Chinese trading firm Kwong Nam Tai & Co. It was gabled at the front and back with a raised, central gable and hip roof allowing for ventilation. The glazed tiles were donated by one member of the Chinese community.

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The tiled roof and mortared ridge rolls were guttered so that rainwater flowed into four receptacles piped to flow out of the mouths of four earthenware fishes. The roof was ornamented on the ridges and barge rolls with elaborate ceramic figures representing historical and mythological Chinese characters. The prayer chimney was considered a masterpiece of angles and water collection, where even driving rain did not enter its open sides.

Holy Triad Temple plaque.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The temple roof.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Plaques inside the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Lantern inside the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The interior comprised three sections: a gatehouse, a courtyard, and an altar. The doors and windows were designed to remain open, inviting in the elements. The internal pillars were designed to be imperfect as a reminder of life's imperfections. The interior was elaborately decorated with exposed carved and gilded timber, and furnishings such as silks, embroideries, lanterns and lamps.

The original forecourt remained incomplete in a skeletal form, demonstrating a divergence from traditional feng shui principles, and indicating limited funds. The only decorative item in the forecourt was a large stove on the western side of the temple, which was later removed to construct the caretaker's house. Although the structure of the spirit wall, yang bi, opposite the temple's main entrance was completed at the time of the temple's construction, it remained undecorated and therefore incomplete.

References

- Amos, J & B. Caretaker's 1976 descriptions of the Holy Triad Temple accompanying photographs. John Oxley Library, box: 16277. 2010.

- Fisher, J. 'The Brisbane Overseas Chinese Community 1860s to 1970s: Enigma or Conformity'. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.

- Queenslander. 30 January 1886, p. 186

- Queensland Heritage Register. The Holy Triad Temple, ID: 600056, 2013. Week. 16 January 1886, p. 10.

It is possible that the man holding the flag in the 1886 image is Sum Chick Tong.

(John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg: 10124, 2013)

The design style of the Holy Triad Temple

The Holy Triad Temple's exterior and interior are presented in a traditional Chinese style that may not have been surpassed in its adherence to conventional Chinese temple architecture in Australia. The only obvious departure from traditional styling that linked the temple to its Australian environment was the original, approximately three metre high, galvanised-iron perimeter wall. From the outside, the Temple appears quite small, which may have been accentuated by the forecourt never being completed; however, the interior of the Temple gives the impression of a much larger building.

The Holy Triad Temple roof

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The Holy Triad Temple's roof distinguishes it from other temples in Australia by its level of adherence to the traditional incorporation of materials, form, colour and style required by the balancing of the feng sui yin and yang forces. This balance is intended to ensure that heavenly blessings are bestowed upon its worshippers. The Holy Triad Temple's roof ridge and ornaments are the most ornate of any Chinese temple constructed in Australia in the late-19th century.

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The bamboo-shaped, green glazed tiles were imported from China and maintain their bright colour. The carvings and ornamental pottery features along the ridge lines above the centre of the gatehouse and altar roofs represent sacred animals and ancient mythology. Each ridge carving incorporates nine blocks, with blocks two and eight of the gatehouse roof bearing the date of the Temple's establishment. While these carvings were originally very bright and colourful, the influence of constant weathering has reduced the remaining colours to green, blue and light brown.

The Holy Triad Temple entrance

The Temple's name San Sheng Gong, translated as the Holy Triad Temple, is located above the main entrance. Although the choice of three gods possesses symbolic significance in both Chinese Buddhism and Daoism, the word gong and the choice of gods worshipped in the Holy Triad Temple suggest the temple initially adhered to Daoism.

The entrance to the Holy Triad Temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The notion of triad is complex, making reference to the three lights of the sun, the moon, and the stars; the three original powers of heaven, earth and water; and the three human elements of body, heart and mind. The Temple's religious creed was founded on the principle of the correlation of heaven, earth and man. The worshipping of the three gods respects the unknowable beginning, middle and end of existence.

The Holy Triad Temple main doors.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Two vertical wooden panels are located either side of the main entrance. They are painted red with large black characters. The panel on the right hand side of the entrance, guan de tong qian li, translates as 'holiness and virtue travel thousands of miles'. The panel on the left hand side, shen en bian wan fang, translates as 'the kindness of God spreads to all corners of the earth'.

The Holy Triad Temple gatehouse

The Temple's main entrance opens into the gatehouse. The stark white walls of the gatehouse are adorned with banners and hangings. The bare red painted floor continues throughout the Temple. Red is a significant colour in Chinese temples, signifying strength. On the left of the gatehouse are two deities positioned on a small altar. On the right side of the altar, Tu Di is the Earth God, otherwise known as the Local God. Fook Tack, sitting on the left of the altar, is a student guardian in studying.

The Holy Triad Temple courtyard

The gatehouse enters into a small covered courtyard. The courtyard provides a transitional zone, and is intended as a gathering space for worshippers. Tables and chairs for worshippers are positioned to the right of the courtyard. A door to the left of the courtyard leads to the caretaker's residence. This door has come to be used as the regular entrance to the Temple.

A Chinese woman in the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The courtyard is framed by four square pillars rising above the Temple's walls to support the raised, central open roof. The characters written on the faces of these pillars exhort moral behaviour. The open roof is designed to allow the natural elements of air, rain and sun to penetrate the Temple so as no man-made barrier exists between the worshippers and nature.

The Holy Triad Temple altar

A gong (luo) was played outside the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

A woman was playing the drum (gu).

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

At the northern end of the Temple, the altar section is on a raised floor to designate its significance, and can be approached from the left or right of the courtyard. A drum gu is positioned in the left aisle, and a gong luo is positioned in the right aisle. The drum and gong are used for entertainment, spiritual devotion and to frighten evil spirits away during formal ceremonies.

The altar section which comprised three altars.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The altar section comprises three altars, dedicated to the three main deities. On the left, Wha Thor (also Hua Tuo) is the God of Healing, being the protector of health and creator of herbal treatments for human ailments. In the centre, Wah Gong (also Hua Guang) is the God of Knowledge, being the creator of humanity's scientific knowledge. On the right, Choi Bark Sung Gwun (also Cai Bo Xing Jun often referred to as Cai Shen) is the God of Prosperity, being the auspicious bearer of wealth and great treasures.

The elevated presence of Wha Thor, Wah Gong and Choi Bark Sung Gwun in a Daoist temple is unusual, as they are not generally considered as important as the Daoist Gods Yu Huang (the Jade Ruler), the Eight Immortals, and Guan Di (the God of War). While these principal and popular Daoist gods are represented in Daoist temples constructed throughout Australia in the 19th century, they are not represented in the Holy Triad Temple. The decoration of the three gods residing in the Holy Triad Temple suggests their careful selection; however, the reasons for their selection remain unknown.

Wah Gong (also Hua Guang), God of Knowledge.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Wha Thor (also Hua Tuo), God of Healing.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Each of the gods, Wha Thor, Wah Gong and Choi Bark Sung Gwun, are decorated with embellished fabric garments. They are each enclosed by large carved gold leaf wooden frames. Gold is chief among the sacred five elements system of feng sui - gold, wind, fire, water and earth. The banners hanging on the altar frontals are embroidered with the cosmological feng sui symbols of a dragon and phoenix amongst clouds, representing the dualism of yin and yang. The dragon is associated with water as the basis of life and the phoenix with love and happiness, which brings peace and prosperity.

The altar section, 2017.

Chinese worshipper in temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Above the three gods, a pair of horizontal wooden panels are inscribed with Chinese characters stating: you wo tong ren - 'may all our people be blessed'; and lai ji wan fang - 'that extends to every corner of the earth'. A table is placed before each of the gods. Each table holds traditional items, such as incense burners, oil lamps and statues. In front of these tables, stands a larger table upon which sit similar items, but including divinity sticks, and food and drink offerings to the gods. This larger table is decorated with wooden flowers and trees carvings of the plum li symbolising long life; the orchid lan symbolising love and beauty; bamboo zhu symbolising endurance and virtue; and chrysanthemum ju symbolising happiness.

References

The entrance to the Holy Triad Temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

A Queenslander journalist attending the Holy Triad Temple's opening ceremony gave the most detailed description of the temple at the time. As a European, he described objects as they appeared to him, not understanding their meaning. What follows is a summary of his description:

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The roof tiles.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The chinaware roof detail, features great men of China's past seated at both the northern and southern ends of the building. These figures represent knowledge of 100 years in the past, and 100 years into the future. The front detail representing ancient Chinese life groups Kings, Emperors, Mandarins, Courtiers and other dignitaries together in a striking and picturesque scene.

A warrior stands defiantly poised with javelin and gold-coloured shield. A king with a waist-length thin beard sits on his throne. A lady with a captivating smile waves her painted fan, while a group of magnificently attired figures clustered together. Others were adorned with features of hope, fear, despondency and joy.

A fish with enormous tail.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

The Holy Triad Temple main doors.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

At each gable end of the building, a porcelain female figure of ravishing beauty sits gracefully with a gilt flute held between dainty tapering fingers, and a large fish with enormous tail and fins curled to the air at their feet. In the centre of the roof, and between the two fish, is a low broad spire surmounted by a small painted globe. The ornamental rooves were imported from China by Kwong Nam Tai & Co., and erected by Chinese artisans.

The entrance to the temple is protected by a small veranda. Suspended from the veranda, either side of the door, hang two globe-shaped lanterns donated by Lum Sing. There is wood carved writing above the door and imprinted tablets either side of the door. Among other instructions, the writing directs those wishing to enter the temple to first be dressed in their best clothing, and to be clean in both flesh and spirit. They must be contrite and bear no ill-intentions towards others.

To fail to do so, risks eternal torment, while the just devotee is received with open arms. The tablets instruct that the Joss knows the visitors' deepest thoughts, and their every action from birth and into the future.

Having entered the building, in niches to each side sit carved wooden cases adorned with gold leaf and with large burnished suns atop. The cases are sat on tables against the walls.

In the niche to the right of the entrance, an artist brought out from China has painted a scene of a bird sitting in a tree growing on the side of a mountain. The bird gazes at the sun breaking through cloud on the back wall. A similar image is painted within the niche to the left, revealing a larger bird with more beautiful plumage.

Interior of the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Interior of the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Red tablets displaying philosophical maxims and proverbs hang on the walls. The interior red and gold decor is furnished with elaborate carved and gilded woodwork, and incense stick holders. Silk drapes embroidered with satin hang from the roof, with some attached to the walls. In the centre of these drapes are symbols worked in black velvet edged with gold.

Decorative lantern in the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Decorative lantern in the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

A woman was playing the drum (gu).

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Large lamps and lanterns of various shapes and colours also hang from the roof. From a cross beam running through the centre of the temple, and to one side, hangs a large, tongue-less bell on a strong chain. To the opposite side, a tubular-shaped drum stands on a tall wooden rest. The drum has a glowing sun daubed in the middle of the ox-hide covering.

An alter extends across the width of the building at the far end of the temple. It consists of three niches made of frail woodwork carved into fantastic devices, and adorned with gold leaf. A large burning sun surmounts the frame of each niche.

A dragon painting at the gate wall inside the temple grounds.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

A fabulous animal with a terrifying aspect is represented in the background of the centre niche. It has goat-like legs, a scaled dog-like body, and a dragon's head with its mouth open to display four fangs and a fiery tongue. Its eyes glare as if the eyeballs seem ready to burst out of their sockets. The beast gazes intently at the sun surrounded by empurpled clouds. The niches either side present scenes of beautiful spreading trees adorned with birds of all sizes and colours.

Upon the altar, butterfly and dragon, hummingbird and bird-of-paradise, and flowing bearded-cheek and ferocious warrior are each placed side-by-side without apparent reason. Near the altar, a collection of traditional military weapons made from led are arranged in racks.

References

- Queenslander. 30 January 1886, p. 186.

- Week. 16 January 1886, p. 10.

The Holy Triad Temple opened on 20 January 1886. The festivities including a feast and fireworks, were open to Europeans as well as Chinese under the provision of maintaining appropriate conduct. The celebrations were repeated on 4 February for the Chinese New Year.

Although influenced by prejudice and patronising in its unedited description, the most detailed account of the temple's opening ceremony comes from an attending Queenslander journalist, who describes:

On the eve of the temple opening, the men preparing decorations and completing finishing touches were rushing to be ready. Chinese butchers had slaughtered approximately a dozen pigs and a number of fowls. The pigs were cooking in a specially constructed large brick oven in one corner of the grounds. At 6 o'clock, the work ceased for a meal of boiled rice with pork and fowl. The workers drank strong black tea and Saki toasts.

At 7 o'clock, with a full moon rising over the wooded heights of Toorak House, Ah King, Lum Sing and Shin Fooie produced a small drum, a pan gong and a pair of large cymbals. Shin Fooie led the harmony for over an hour, gradually rising from gentle tapping and clapping to being loud enough to draw the people of the neighbourhood pouring into the yard.

The initial 'loafer' and 'larrikin' arrivals were soon followed by mothers with babies, along with young women and workers who were washed and had settled in for the night. The gathering crowd mingled with the Chinese pouring questions on them about the occasion.

Through the night, the Chinese remained hospitable towards the Europeans, treating them as guests and providing them with alcohol. Numerous Europeans took advantage of this hospitality by consuming more than their share of the available liquor.

Around 11 o'clock, Sum Chick Tong arrived with a group of dignitaries bearing his own splendid £50 green silk flag, representing the Royal Dragon of the Chinese Empire. Chick Tong's flag was hoisted up a waiting pole between two other red flags with white mitred borders.

At this point, the dignitaries requested the European onlookers leave so that the final preparations could be completed. Anticipating a startling event at two in the morning, the Europeans remained outside the grounds speculating and yawning, and enjoying a dry, warm moonlit night.

Worshippers in the Holy Triad Temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Inside the temple, the scene was dressed in striking and imposing grandeur. The interior was ablaze with light, making the altar that glittered in daylight dazzling at night. The perpetual lamp before the altar's central niche had been lit. All the hanging lamps, chandeliers, and lanterns gleamed and blazed.

Spiral bouquets of artificial flowers were placed upon the altar. They were created with golden-hue tinsel and innumerable peacock feathers of rare beauty. Over these bouquets, and the mass of gold which had been worked into the altar frame, fell the effulgence from thousands of tiny papers placed in silver urns.

An object covered in crimson-coloured paper had been placed in each altar niche, and in those near the entrance. Small pyramids of rice, plates of food, and cups of tea and Saki were also placed on the tables near the entrance. Three cooked pigs lay on a table in the centre of the temple, between which and the altar stood a further carved, gilt and ornamented table.

On this gilt table sat further artificial flowers and feathers in five oddly-shaped silver-gilt vases filled with sand. Amidst these vases was a small square rack, containing twelve prettily painted bannerettes. A short wooden sword in a paper sheath was placed in the centre. A smaller table stood near the altar. It was covered in a variety of foods including rice, fowls, pastries, tea and spirits.

At approximately one-thirty in the morning, the night erupted with crackers and bombs, as a 30 foot fireworks rope running up a high pole was set alight. For seven minutes, the fireworks rope showered sparks and flooded the grounds with smoke. Fifteen minutes after the fireworks started, loud music commenced and the doors of the temple were opened to welcome a procession of the waiting Chinese.

A gong (luo) was played outside the temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

A young man beating a gong led the procession, followed by Chick Tong and George Shue bearing between them a half-rolled, small strip of cloth. A magnificently embroidered and embellished canopy of the richest material was held over their heads. Above this was an enormous leaf-shaped fan of similar material.

Chick Tong and Shue were followed by the temple monk, an old man dressed in red flannel with chintz borders and a rural scene painted over the small of his back. The monk wore a black cap with a red border and a gold knob on the crown. He held a circular iron plate which he continued to beat with all his might.

The remainder of the Chinese participants followed, beating drums and gongs and playing reed instruments as the fireworks continued outside. Upon reaching the altar, Chick Tong and Shue unrolled the cloth. They hung it, covering the body of the dragon in the altar's central niche. Immediately, the crimson papers that had been covering the objects in the niches were removed, revealing bronze idols.

The procession then knelt on the floor, touching the floor three times with their foreheads. The monk dipped a branch in a bowl and anointed the idols, the altar and the surrounding temple as he softly spoke an incantation.

Way Hop entered with a cock that was bled from the comb. The monk used the blood to again anoint the idols on various parts of their bodies while chanting a further incantation. This was an act of life entering the statues. As the monk anointed the idols, hundreds of further tapers were brought into the temple and added to those already alight.

The drums, gongs, and reed instruments recommenced until directed by the monk to cease. He proceeded to anoint all the statues in the temple again while continuing to chant incantations. When the monk had finished, the congregation began genuflecting rapidly while printed gilt paper was burnt. The temple by this stage was close and stifling. It was as hot as an oven, full of smoke, and bore the strong scent of candle tallow and roast pork.

As the smoke cleared, the monk could be seen standing before the altar, chanting in a louder voice, while the trustees of the temple, Chick Tong, George Shue, Way Hop, Wam Yo and Tong Wah knelt behind him. The monk informed the Trinity who the trustees of the temple were and invoked their protection from evil.

Poe divination - a traditional Chinese divination method.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

At three in the morning, the monk tossed two pieces of wood into the air to see if the Spirit had come among them and intended watching over the Chinese community. The trustees studied the pieces of wood closely as they fell to the floor. After seven attempts there was a favourable reply, to the gratitude of all gathered. The trustees bowed to each other with clasped hands and the service ended.

For almost the next 60 years, the temple remained the focal point of Brisbane's Chinese community's activity.

Holy Triad Temple plaque.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Chinese worshipper in temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Chinese worshipper in temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Chinese worshipper in temple.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Burning joss sticks.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Wah Gong (also Hua Guang), God of Knowledge.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Choi Bark Sung Gwun (also Cai Shen), God of Prosperity.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Chinese woman burning joss paper.

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

Chinese woman doing kau chim [lottery poetry].

(John Oxley Library, Amos photography collection, 1976)

References

- Fisher, J. 'The Brisbane Overseas Chinese Community 1860s to 1970s: Enigma or Conformity'. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.

- Maryborough Chronicle. 18 March 1886.

- Queenslander, 30 January 1886, p. 186.

- Queensland Figaro. 4 December 1902, p. 3 (7).

- Queensland Heritage Register. The Holy Triad Temple ID: 600056, 2013.

- Week, 16 January 1886, p. 10.

European responses to the construction of the Holy Triad Temple were mixed. The involvement of Brisbane's premier building firm, John Petrie and Son, caused controversy and drew much criticism. Although the temple's construction was dwarfed in comparison to Brisbane's construction boom, it also generated considerable interest from Brisbane's residents. Many would deliberately pass the Breakfast Creek construction site as they took their Sunday walks.

Four days prior to the temple's completion and opening, the residents of Brisbane crowded around to watch the Chinese artisans at work. The arriving and departing onlookers dangerously overloaded Brisbane's recently installed tram system. Horses drawing trams returning to the city were whipped, while men pushed the cars, to get the trams moving.

Four days after the opening ceremony, Rev. Osborne of the Anne Street United Methodist Free Church delivered a sermon understanding the right of the wealthy Chinese to build a temple for their countrymen. However, Osborne condemned the hideous idolatry of the new Chinese Joss-house, as almost surpassing that of Roman Catholics. For Osborne, the temple was testament to the failure of Christians to convert Brisbane's 1000 Chinese. He called for a missionary program to convert the heathens, cast out their idols, and for their temple to become a place of Christian teaching.

In the 1880s, the Chinese community were Brisbane's most ostracised minority. However, they remained welcoming and hospitable to all who wished to be present at their ceremonies, sharing food and alcohol, and answering questions. While most Europeans respected behavioural expectations, numerous people took advantage of the Chinese community's hospitality as a chance for free liquor. The temple and its worshippers were also occasionally prone to insults and assaults from a vocal minority of usually young and intoxicated men known as larrikins.

The most notorious night in colonial Brisbane's history revealed the very real danger that the Chinese community and the Holy Triad Temple faced from their detractors. On 5 May 1888, the Brisbane riot escalated quickly from approximately 50 teenagers to over 1000 people vandalising Chinese boarding houses and businesses in the City and the Valley. The call rose to destroy the Breakfast Creek Joss House, but the majority considered this too far away.

Anti-Chinese violence dwindled from the public eye after the Brisbane riot. The following Chinese New Year celebrations on Wednesday 30 January 1889 saw continued European support. The festival proceeded in the following days with the customary Chinese liberal hospitality towards any Europeans that joined them. Even when through simply curiosity.

References

- Brisbane Courier. 1 February 1886, pp. 4 (6).

- Brisbane Courier. 15 March 1886, p. 4 (8).

- Brisbane Courier. 8 May 1888, p. 4.

- Brisbane Courier. 1 February 1889, p. 4 (7).

- Fisher, J. 'The Brisbane Overseas Chinese Community 1860s to 1970s: Enigma or Conformity'. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.

- Maryborough Chronicle. 18 March 1886.

- Queenslander. 12 May 1888, p. 746.

- Queensland State Archives. Digital Image ID: 1910, 2013.

- Rains, K. 'The Chinese question', Queensland Historical Atlas, 2010.

- Telegraph. 25 January 1886, p. 5.

- Week. 16 January 1886, p. 10.

- Week. 29 January 1887, p. 7 (3).