Deterioration

European racism driving the white Australia movement threatened the temple with acts of vandalism, souveniring and threatening its worshippers with abuse and assaults. A diminishing Chinese population, generational change and remoteness became the ultimate threats to the Holy Triad Temple, as second-generation Chinese migrants adopted western customs.

Albert Street, Brisbane, 1883.

On the night of 5 May 1888, a riot began around eight in the evening when a large group of drunken youths congregated in the Exchange Hotel witnessed a dispute over payment between a Chinese businessman and a white youth. The group assaulted the businessman, stole his purse and other possessions, and shattered the windows in his store, stealing tobacco, cigars, pipes and other articles. The youths marched down Charlotte Street to Albert Street sacking and looting every Chinese owned store and lodging house in Old Frog's Hollow.

The riot passed through the city half a dozen times increasing in numbers. The most active group in the crowd numbered approximately 50, of which the majority were aged between 14 and 18 years old. However, the number of participants rapidly grew through the riot, reaching approximately 600 by nine-thirty, and up to 1000 at its zenith.

At one point the call of 'Kwong Nam Tai' sent the riot towards that business in Queen Street, but it was protected by the police. Likewise, a later second attempt to attack Kwong Nam Tai was prevented by the police presence.

The 3.6 metre high plate windows at Soy Chow Loong & Co. were shattered by road mettle with the intention of looting the store until word passed around that there was an armed Chinese man inside. The mob fled with some handkerchiefs and returned down Albert Street, again stoning every Chinese shop and boarding house.

The mob returned back up Albert Street to Queen Street. In Queen Street, the third attempt to sack Known Nam Tai was again held at bay by the police presence, but the mob managed to break some windows. The police presence, while not responding to the riot, was enough to reduce the damage.

The mob then headed for George Street, where they smashed the windows of Sun Wing Chong's shop before rushing towards Wai Sang Loong's shop near the railway gates, again smashing plate glass windows. One youth was arrested, but immediately released by the over-powering presence of the mob.

A call came to attack the Chinese businesses in the Valley, and so the mob charged towards Roma Street and then down Ann Street. The ring-leaders reached a Chinese furniture manufacturer near the Excelsior Hotel first. They destroyed many windows before the rest of the mob arrived. They then marched on to the large On War Tai & Co. store in Wickham Street, where the shutters were closed. The mob destroyed the windows on the second floor.

Nearing midnight, the call rose to destroy the Breakfast Creek Joss House, but the majority were sobering up and thought it was too far. The mob returned up Wickham Street to Queen Street with the excitement abating and only about 100 rioters left. They discovered mounted police waiting in Queen Street, in face of which the group lost energy and returned to their homes.

It was noted by the Chinese of Brisbane that the rioters were predominantly youths. Although the event left them in a serious state of consternation and worried about the potential of recurring riots, it was understood that the youths did not meet the approval, nor represent the wishes of the community's more respectable members.

Anti-Chinese violence diminished from the public eye after the Brisbane riot. However, the Brisbane and Stanthorpe importing company Kwong Nam Tai & Co. filed for insolvency the following year, citing irreconcilable debts, reduced trade owing to anti-Chinese sentiment after the riot, and losses in the 1887 flood, among numerous issues.

References

- Brisbane Courier, 15 March 1886, p. 4 (8).

- Brisbane Courier, 8 May 1888, p. 4.

- Brisbane Courier, 8 May 1888, p. 4.

- Queenslander, 12 May 1888, p. 746.

- Queensland State Archives. Digital Image ID: 1910, 2013.

- Rains, K. 'The Chinese question', Queensland Historical Atlas, 2010.

Chinese Dragon painting on temple wall.

On the night of 5 May 1888, a riot began around eight in the evening when a large group of drunken youths congregated in the Exchange Hotel witnessed a dispute over payment between a Chinese businessman and a white youth. The group assaulted the businessman, stole his purse and other possessions, and shattered the windows in his store, stealing tobacco, cigars, pipes and other articles. The youths marched down Charlotte Street to Albert Street sacking and looting every Chinese owned store and lodging house in Old Frog's Hollow.

In the early years, the Holy Triad Temple was seen among some Europeans as a centre of hope, faith and nobility that compelled admiration. Although the temple was dedicated to Buddhist worship, Confucian Chinese were equally welcome at a common altar in a unity that was not shared by Brisbane's Christian denominations. Devotees prayed once a day in the temple, and aside from significant ceremonial occasions, gathered for the first and fifteenth of each month.

This perception of nobility challenged contemporary anti-Chinese rhetoric about superstition and barbarism that dominated arguments for a white Australia. The late-19th-century, white-Australia movement gathered momentum as the century came to a close. During this time, Chinese residents were continuously under threat of abuse and physical violence. One such example occurred soon after the temple opened.

At 9 o'clock on Sunday evening on 14 March 1886, a larrikin within a group of European onlookers assaulted a temple musician during a ceremony. As a result, the Chinese rose as one and struck out at the onlookers with their forms and stools. As the Europeans attempted to escape, the gates were closed, trapping many inside, including women and children.

Although the larrikin was briefly cornered, he managed to escape. However, the remaining Europeans were detained until the Chinese were convinced of the larrikin's escape. During the fracas, the Europeans outside the grounds attempted to break down the gates to free those trapped inside. The Chinese kept them at bay with various missiles hurled over the fence.

Racist values continued to inform attitudes towards the Chinese that justified vandalism and souveniring into the mid-20th century. The first physical threat to the temple of this kind came in 1888, when approximately 1000 drunken rioters attacked Chinese businesses and residences throughout the City and the Valley. Calls to destroy the temple failed to materialise into action due its distance from the Valley.

On another occasion, in the days before the 1907 Chinese New Year, European larrikins rained large stones on the temple roof, destroying one of the china statues. In the face of such hostilities from sections of the community, the Chinese continued to maintain their peaceful presence.

The Chinese remained renowned for their generosity during New Year celebrations, even for those who would do them harm. European guests and onlookers were still welcome to attend the 1907 celebrations. The temple continued to remain open at all times for all visitors, leaving it prone to being taken advantage.

For example, in June 1925, a 42-year-old wharf labourer named James John Roberts, alias James Gillian, was convicted of stealing three carved figures from the temple. On the day of the robbery, the caretaker Lum Yowe had been absent, and a neighbour had been responsible for sending her young daughter to alert the police. A previously convicted thief, Roberts was arrested at the Breakfast Creek Hotel, having hidden the statues near an outhouse.

Although Roberts claimed he was drunk and his actions were more for amusement than anything else, he was sentenced to one month's imprisonment with hard labour for robbing a house of worship. The items were given extra value by the court, as they were only able to be manufactured in China by specialised workman using specific materials.

By 1948, after years of vandalism and souveniring, especially during World War Two, the Holy Triad Temple had been walled up and deserted.

References

- Brisbane Courier, 15 March 1886, p. 4 (8).

- Brisbane Courier, 8 May 1888, p. 4.

- Brisbane Courier. 14 February 1907, p. 5.

- Queenslander, 12 May 1888, p. 746.

- Queenslander, 4 April 1903, p.750.

- Queensland Figaro. 4 December 1902, p. 3 (7).

- Queensland Times. 10 June 1925, p. 4.

- Sunday Mail, 29 February 1948, p. 3.

- Telegraph. 9 June 1925, p. 2.

- Week, 16 January 1886, p. 10.

Although George Shue originally owned the land on which the temple was built, the belief the land was owned by a European persisted. This may be due to George Shue taking out mortgages from European brokers against the temple's land, as no Chinese appeared willing to provide Shue financial aid. While considered a leader in the Chinese community by the Queensland Government, and a notable at the opening ceremony, Shue played no further part in the temple after its opening.

In 1902, successful Chinese merchants Mee Lee, Lee Chow, Lee Gun, Tong Lee, Jim Yin, Fat Kee and See War commenced a bid to take possession of the land in order to protect the longevity of the temple. While this bid failed, according to the Register of Titles, Jue Yow, Jim Yin, Show Pan, William Yek Loong, Lee Chow and Mee Fook took ownership of the land in 1903. None of these tenants chose to pass their ownership on to heirs. The land title officially remained in their ownership until it was conferred upon the Chinese Temple Society by the Queensland Government in 1964 as a result of no known surviving tenants. However, by 1935, the threat to demolish the Holy Triad Temple and sell the land on which it stood manifested due to overdue council rates and the Temple falling into disrepair.

By 1935, the temple sat in the shadow of the neighbouring Albion Park racecourse grandstand. It had lost much of its colour and was looking weather beaten and damaged by vandalism. However, some of its past glory could still be witnessed in the exterior wooden carvings, porcelain rooftop figures and the Chinese writing at the entrance reminding the worshiper to be clean of mind and body.

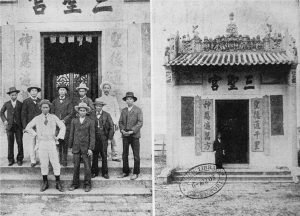

Some Chinese citizen of Brisbane and Holy Triad Temple.

References

- Courier Mail. 13 September 1935, p. 12.

- Courier Mail. 18 September 1935, p. 15.

- Daily Standard. 18 September 1935, p. 2.

- Daily Standard. 10 March 1936, p. 10.

- Fisher, J. 'The Brisbane Overseas Chinese Community 1860s to 1970s: Enigma or Conformity'. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.

- Queensland Figaro. 4 December 1902, p. 3 (7).

- Telegraph. 17 September 1935, p. 21.

By the mid-1930s, almost 50 years after the temple had opened with its extravagant splendour, barely 100 older Chinese remained in Brisbane. The numbers of elderly Chinese were diminishing each year, and fewer worshippers were attending the temple quietly following traditional customs and praying. These diminishing numbers can be equated to the effects of Government policy, a gender imbalance caused by the virtual prohibition of Chinese females entering Australia, and the sojourner intent of Chinese migrants. As a result, fewer people remained to care for the temple.

Although the traditional Chinese New Year continued to be observed by some, the Holy Triad Temple was no longer the scene of past celebrations. The festivities had been reduced to a brief fireworks discharge at midnight, with feasting in their own homes, and ceremonial visits to old friends. The once splendour and extravagance, with joyous celebrations and a public holiday followed by days of visiting family and friends were over.

However, the temple remained in limited use, with the traditional services on the first and fifteenth of each month continuing to be held by the temple's priest or warden.

The temple was otherwise deserted by worshipers and monks.

Holy Triad Temple in 1934.

To the general public, it had come to be seen as clouded in mystery behind the ramshackle cloak of its fence. The Holy Triad Temple was now considered old and strange, with quaint, weird and mysterious carvings and painted porcelain tilings. It was deemed a colourful relic of old China. By 1948, after years of vandalism and souveniring, especially during World War Two, the Holy Triad Temple had been walled up and deserted.

When interviewed about the temple in 1948, the then Chinese Consul Mr Cheng revealed he knew nothing of the temple, he had never visited it. Cheng added that the older Chinese community who may still have retained their traditional beliefs, now lived so far away from the temple, they could no longer make the journey to it, and all its idols had been removed.

Cheng's claim that no Chinese had visited the temple for many years, was misleading. A handful of the older Chinese had continued the tradition of attending the Holy Triad Temple. Although, a neighbouring resident, named Tommy Foo noted that few people attended the temple except for special Chinese occasions.

The majority of Brisbane's Chinese community by the 1930s were English-speaking, Queensland natives who celebrated western customs, holidays and feast days. These Queensland-born Chinese had generally adopted Christianity. They celebrated the western New Year in keeping with other world nations. This may have resulted from endeavours to be included in Australian society, and these children, by being excluded from government schools, attending fee-paying religious schools.

By 1951, Brisbane's approximately 500 to 600 Chinese population were again celebrating their traditional New Year. These celebrations were now in the form of a boat picnic or a dance. Organising secretary of the Chinese Citizens' Association Mr W Sou San confirmed that the younger Chinese had turned to more Australian ways.

Second generation, Australian-born Chinese were not interested in the old customs, and tended to share a meal for the New Year and then forget about it. While beer and whiskey were drunk, the celebration no longer extended beyond the eve itself. The younger generation also continued to celebrate the western New Year.

Until the formation of the Chinese Temple Society in 1964, no individual group were responsible for the temple. No central Chinese district or China town had evolved in Brisbane. Chinese businesses and residents had always been scattered around the City, the Valley and in the suburbs. Although the remoteness saved the temple from the 1888 riots, as the local Chinese population diminished, the distance to the temple increased.

In a striking incident on 1 January 1954, New Year's Day embers from fireworks set off in the Holy Triad Temple lodge in the temple's roof soon after two in the afternoon, setting it on fire. Local firemen attending the fire could not stop two altars and the roof being damaged. With the temple in ruins, its contents vandalised or souvenired, only the temple caretaker remained on the site.

References

- Amos, J & B. Caretaker's 1976 descriptions of the Holy Triad Temple accompanying photographs. John Oxley Library, box: 16277. 2010.

- Brisbane Telegraph. 6 January 1951, p. 11. Brisbane Telegraph. 1 January 1954, p. 19.

- Courier Mail. 5 February 1935, p. 12. Courier Mail. 18 September 1935, p. 15.

- Daily Standard. 18 September 1935, p. 2.

- Fisher, J. 'The Brisbane Overseas Chinese Community 1860s to 1970s: Enigma or Conformity'. PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005.

- Sunday Mail. 11 February 1934, p. 7.

- Sunday Mail, 29 February 1948, p. 3.